Conversation 2: Lukas Schmid

Context¶

In March 2025, engineer Lukas Schmid visited my studio in Olten for the second Conversation with Splicer. Unlike the first guest, Lukas comes from a non-artistic background: he works in mechanical engineering within the field of medical technology and has little professional involvement with the arts. However, Lukas played an important behind-the-scenes role in the development of Splicer. Throughout the years, I regularly turned to him for informal advice on mechanical and technical challenges. Several core design decisions, now embedded in the machine’s structure, can be traced back to our conversations.

The invitation for the Conversation emerged from this long-standing exchange. It was a chance not only to acknowledge Lukas’ contribution to the apparatus’s construction, but also to open a reflective space between two different ways of thinking: engineering logic and photographic experimentation.

Photography between Visual Memory and Technical Notation¶

Lukas described his everyday photography as primarily pragmatic. His phone camera is a tool for documenting technical details: e.g., a car part, a door hinge, or a wiring detail—functioning like a visual notebook. At the same time, he acknowledges the emotional value of photography as a trigger for memory, akin to how smell or taste can evoke vivid recollections. The photographs as such are thereby not really an important object other than functioning as this trigger for memory.

«To me, photos are like another visual sensory impression […] a trigger that moves the brain into a situation […].»

Lukas Schmid, April 2025.

The Subjectivity of Images and the Myth of Neutral Vision¶

A recurring theme in the conversation was the tension between objectivity and subjectivity in photography. Lukas reflected on how, over time and especially with the rise of AI-generated and manipulated images, he has become more critical of the intentions behind photographs, particularly in media:

«I used to see the whole thing as more neutral […]. Today I think: there's an intention behind every image.» Lukas Schmid, April 2025.

An important discussion was, whether the perception of photographs has changed because the images themselves have become more constructed or because the viewer now brings greater media literacy and contextual awareness. This led to a shared conclusion: every image is shaped by subjective framing, whether by the photographer, apparatus, or viewer.

Interpreting Splicer and the Role of the Machine¶

Finally, we explored how Splicer, as an apparatus, plays with perception and control. Lukas reflected on how the machine constructs images over time, distorting conventional photographic expectations. Splicer's images may be considered more objective, because they reveal their constructedness, or more subjective, because they are fundamentally unfamiliar and shaped by technical parameters.

This led to a nuanced conversation about the logic embedded in machines, and how understanding those parameters might allow someone to decode what they see. If one knows how Splicer works, the resulting image may become more objective; alternatively, its strangeness may reinforce the idea that all images are interpretive.

The Sample¶

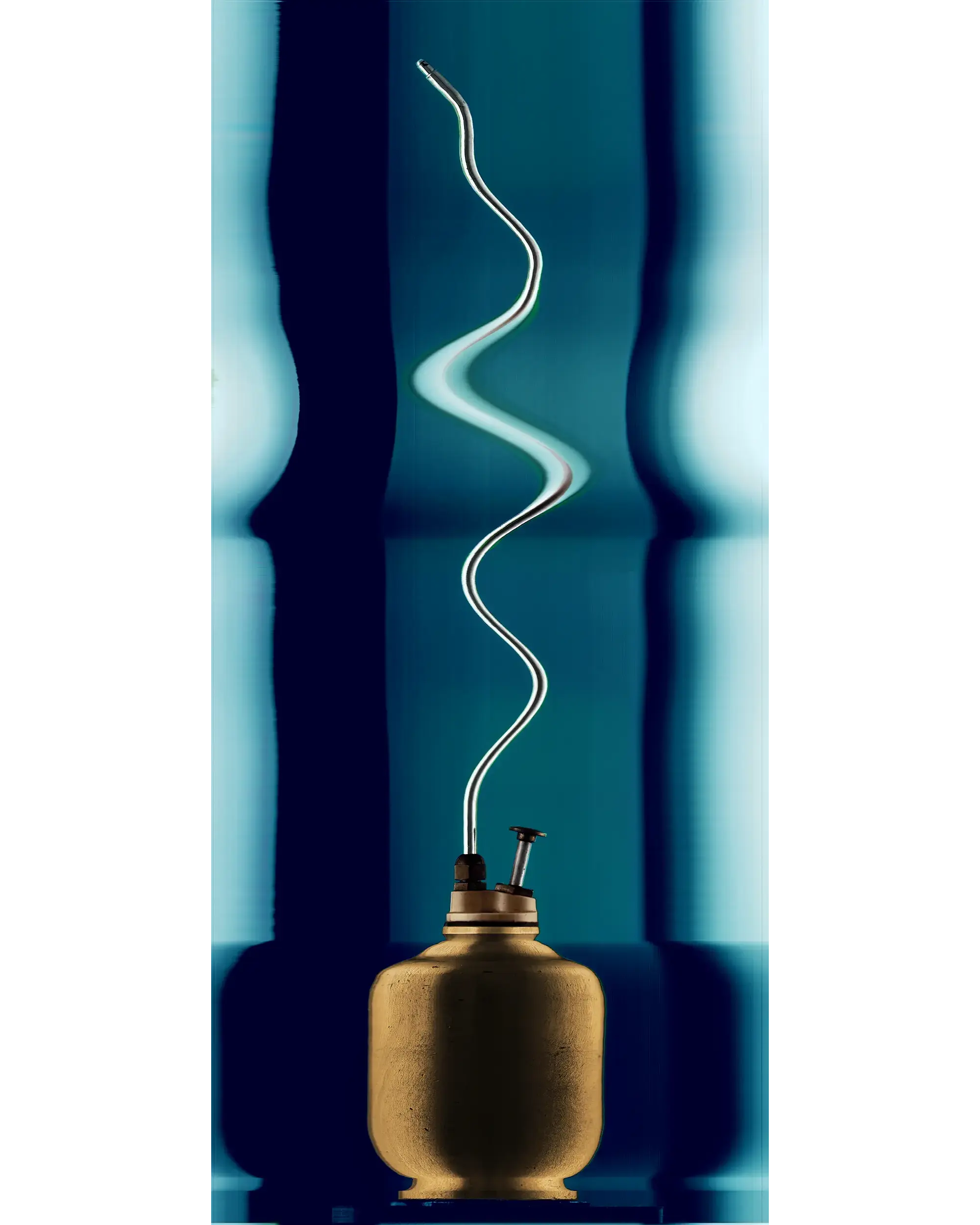

Lukas brought a small oil can, an unassuming but symbolically rich object he discovered early in his engineering career behind a neglected machine. Since then, it has accompanied him, a quiet companion in the background of precision work. This type of tool is used to oil the frictionless linear guideways that enable the controlled, multi-axis movements of CNC and other complex industrial systems. Though this object draws little attention, the oil can is essential to the smooth functioning of large-scale machinery. It stands for the hidden infrastructure of precision, an overlooked tool that quietly sustains mechanical accuracy.

In Splicer, Lukas and I programmed a sequence of movements to sample the oil can. What emerged was a vertically composed image of a transformed object: the can’s body appears bulbous, sculptural, and unexpectedly elegant. The long, flexible dispenser tube becomes an elongated central feature. At times, it appears sharp and articulated; at others, it dissolved into a vaporous blur. As it undulated above the canister, it oscillated between the mechanical and the ephemeral. The background itself carries the visual residue of these programmed motions, recording the gestures that animated it. What began as a utilitarian tool was reimagined as an image-object.