Conversation 1: Charles Kwong

Context¶

In February 2025, composer and artist Charles Kwong stepped into my studio in Olten for the inaugural multi day collaboration with Splicer.

Charles is classically trained composer from Hong Kong with an increasing focus on experimental sound was immediately drawn to Splicer when I told him about the apparatus. Charles' comment during an earlier discussion on Splicer’s conceptual affinity with granular synthesis made him a fitting first collaborator. Granular Synthesis, a composition approach conceptualized by Iannis Xenakis in the 1960ies, is a sonic technique that decomposes sound into tiny fragments (“grains”) that are then recombined to form new auditory textures Xenakis, 1990. Out of this discussion we coined the term Granular perspective as Splicer does something similar as granular synthesis but with the sample, space, and time.

«In working with Splicer, what I find interesting is that it reveals a kind of perception that neither of us could have foreseen. None of us knew what the image would look like at the start – we were discovering it through the process. That’s where I see the uniqueness or value of this kind of image-making: it shows that photography is really about creating something, not just capturing something that already exists.» Charles Kwong, Splicer collaboration debrief, April 3, 2025.

Situated Collaboration as Experimental Method¶

The collaboration between Charles and Splicer unfolded less as a production session and more as a shared experiment, an open-ended exploration shaped by dialogue, iteration, and the physical presence of myself as a helping hand. Rather than arriving with a fixed concept or outcome, Charles approached the machine with curiosity and a striking level of motivation. Charles was eager to test its visual logic through improvisation, experimenting playfully and extensively with different settings and ideas. At times, I even had to slow the process down to avoid getting lost in the sheer range of possibilities.

This engagement fostered a space of mutual exchange. The collaboration became more than an image-making exercise, it was a discursive process that allowed both artists to reflect on their respective practices through the lens of the other. For Charles, the relatively unfamiliar medium of experimental photography echoed aspects of his sonic work; for me, Charles’ insights opened new conceptual paths for reading Splicer’s of creating photographs through a compositional logic. The process proved deeply enriching for both, grounded not in output alone, but in this shared act of exploration.

Temporality and the Shifted Experience of the Photographic Moment¶

In the conversation we explored how photography intersects with the experience of time. Charles reflected on the fundamental difference between space and time: while we can move freely through space, time only moves in one direction. Once a moment has passed, it cannot be re-entered. Photography, he noted, attempts to hold onto this passing, but only ever offers a fragment that can never replicate the immediacy of lived experience.

I added that photography, by its very nature, is always about the past. The moment the shutter is pressed, the present becomes irretrievable. Even practices like live-streaming only simulate the “now,” but they remain rooted in delay. From this, we came to suggest that any art form valuing embodied, real-time experience implicitly critiques the dominant media logic of capture, reproduction, and circulation.

It is in this light that Charles found Splicer compelling. Unlike conventional cameras that freeze a single instant, Splicer accumulates many small fragments of time into one image. Drawing a parallel to granular synthesis in music, he sees this as a temporal layering, a visual accumulation rather than a singular capture. The final image, though static, carries traces of the process that produced it. For Charles, this is where the value lies: not in representation, but in revealing a new perspective, one that emerges through time rather than being extracted from it.

Additive vs. Subtractive Image Construction (and its Sonic Analogue)¶

During our collaboration, we tried to draw parallels between photographic and sonic composition, particularly through the lens of additive and subtractive synthesis concepts from electronic music. In subtractive synthesis, sound is shaped by filtering out frequencies from a rich signal; in additive synthesis, sound is constructed by layering discrete elements to build complexity.

This analogy may become a useful framework to describe different photographic logics but needs further exploration. We observed that in lens-based photography, often the post processing works subtractively: subjects are cleaned, posed, retouched: imperfections are subtracted to reveal a purified image. By contrast, post-photographic practices like computer generated imagery (CGI) or artificial intelligence based image generation (AI) tend to be additive, fabricating images from nothing or layering in noise, texture, and adding imperfections to simulate believable realism.

Splicer may be seen as operating across both modes. It subtracts micro-slices of time and space and then adds them together into a new composition. The result is not a snapshot, but a visual construct that imagines a different continuity. For Charles, this hybrid process resonates deeply with his compositional work, where real-world resonance and abstract construction often merge. The machine doesn’t just capture what is there; it builds something that wasn’t visible before.

The Sample¶

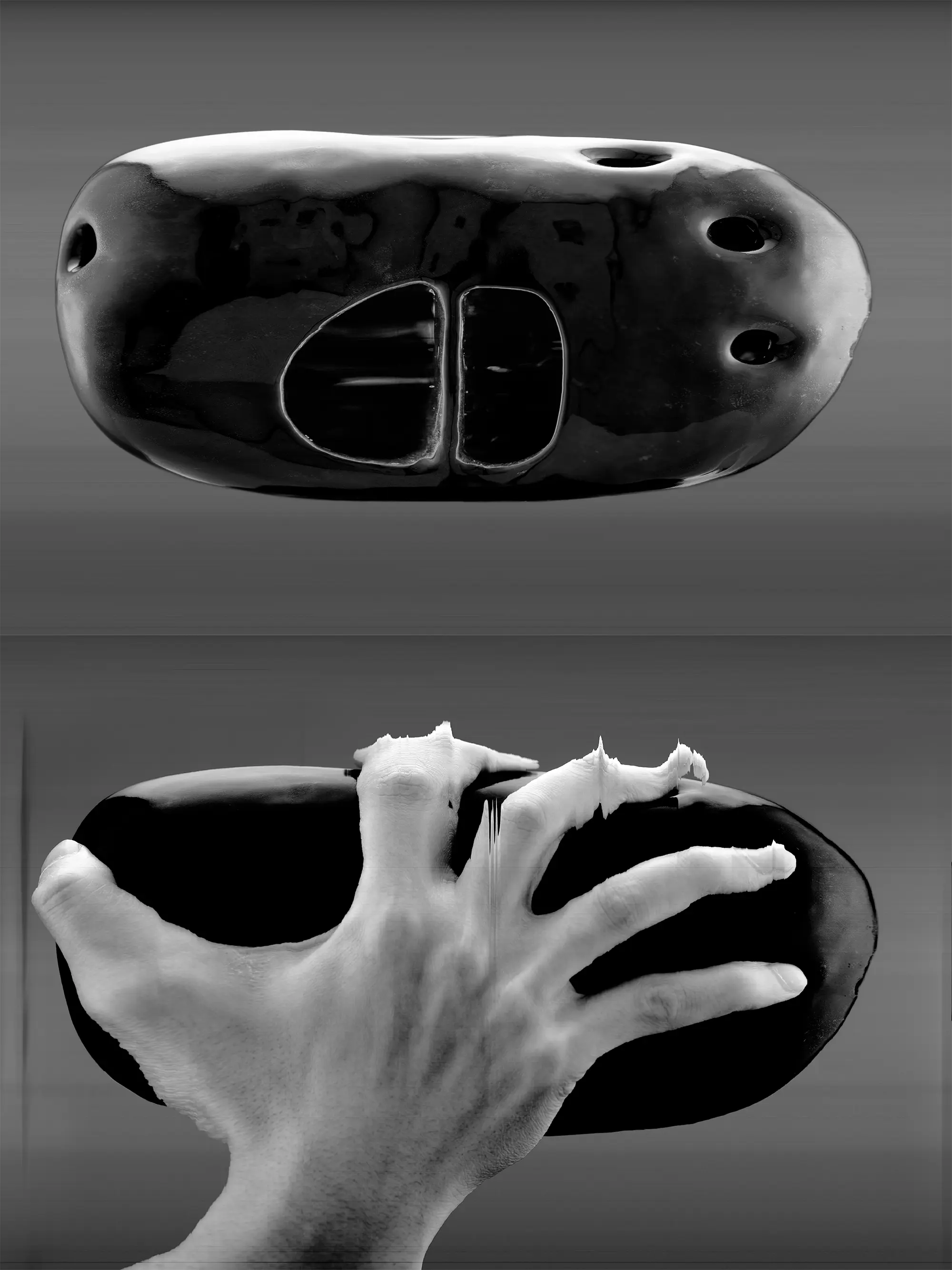

Charles brought one of his hand-built ceramic instruments, developed as part of his recent work in experimental music and transdisciplinary art. During performance, the instrument houses a wireless microphone that creates a feedback loop with a nearby speaker. Unlike conventional musical practices that avoid this unwanted feedback, this instrument embraces it. By moving through space and adjusting the proximity between microphone and speaker, and by covering or uncovering the instrument’s holes with his fingers, Charles modulates the feedback in real time. The resulting sound emerges from a dynamic interplay between body, object, and acoustic environment. Sonically, the instrument functions as a resonant body in space, with qualities reminiscent of a flute.

On Splicer, this ceramic instrument became the sample. The movement of the sample during capture was echoing how Charles would handle the instrument in performance. The imaging process recorded the sample from multiple angles, including the underside and the inside, surfaces invisible performances. A diptych captures specifically this performance: in the top image, the instrument, typically obscured by the hand during performance, appears floating and untouched; in the lower image, Charles’s hand is recorded along as he activates the ceramic instrument. The result is not just a visual document of the object’s appearance, but of its activation: gesture, motion, and intention become embedded in the final image.

Xenakis, I. (1990). Formalized music: Thought and mathematics in composition (Rev. ed). Pendragon press.