Becoming Splicer

The idea of Splicer began in 2018 after I started working at ECAL/University of Art and Design Lausanne and development continued through to 2025 as I completed my Master's at ZHdK/Zurich University of the Arts. Rather than progressing through clearly separated phases, the project evolved through an ongoing, iterative loop of experimentation, reflection, and adaptation. Major advancements occurred in 2020 to 2021 and again between 2023 to 2025 (during the Master Transdisciplinarity in the Arts at ZHdK), each driven by hands-on engagement with the device, its images, and their implications.

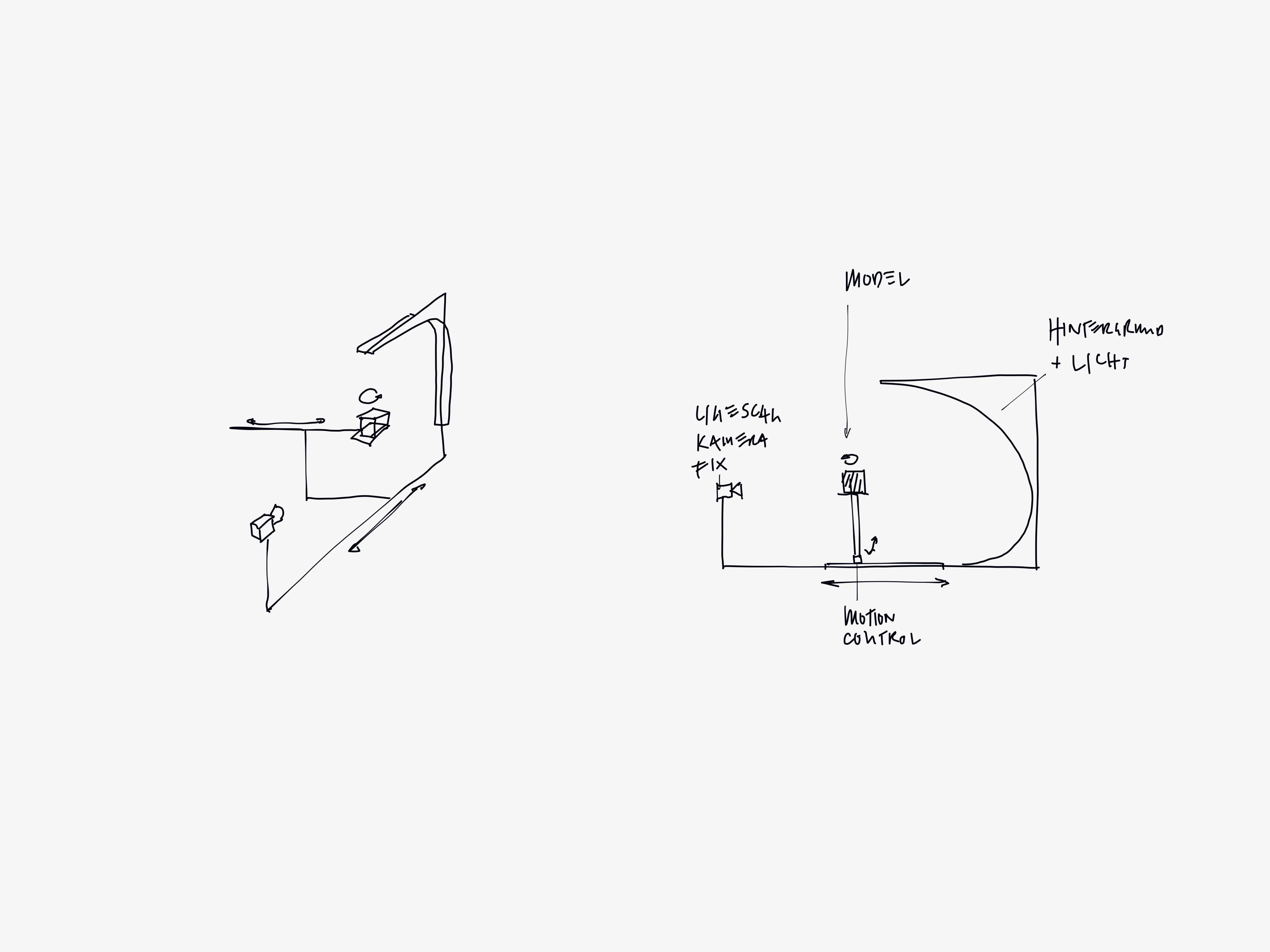

Splicer Concept Drawing, April 2019

The early phase was characterized by a deep investigation into the individual components that make up a contemporary imaging system. Much of this time was spent acquiring the necessary technological expertise, reading through manuals, exploring a range of possible approaches and technologies – and working to fund the project.

What followed was a period of prototyping – and failing – during which the interplay of hardware, software, and aesthetic concerns was repeatedly tested and revised. A first proof-of-concept in 2020/21 demonstrated the feasibility of this configuration. By 2021, a working prototype using three axes of motion confirmed that the chosen approach might indeed support a fully integrated system.

In 2023 and 2024, the addition of a motorized camera lift and a completely rebuilt camera module (v2) expanded the control system to the nine axes originally envisioned. By the beginning of 2025, the project reached a provisional point of completion.

SPLICER / DEVELOPMENT, Splicer Looking at Florian, Autumn 2024

C-print, 40 × 50 cm

The continuous and open-ended process has led to a somewhat peculiar situation. For a long time, I’ve told people that Splicer is working – but not yet finished. In a world that expects clear outcomes and definitive endpoints, such ongoing development was often met with confusion or impatience. Eventually, people stopped asking whether it was done. Strangely, this created a kind of comfortable space: the project continues on its own terms, without the pressure of finality.

I’ve come to accept that Splicer may never truly be finished. It might one day simply be left behind – abandoned in whatever state it has reached, still unresolved, yet somehow complete in its incompleteness. Especially within the context of most of photography, where an image either exists or it doesn’t, a project oriented toward potential photography – a machine for images that might still come – was often met with bewilderment. And perhaps it is precisely this state of perpetual incompletion that keeps the machine alive with possibility: enabling the imagination of latent images still embedded in its logic, waiting to be revealed.